EDITORIAL: Why Hiring and Getting a Job is So Difficult Now

It's been getting worse for a long time, folks, and is unlikely to get better any time soon. Here's why.

Audience: Job seekers, employees, HR personnel, hiring managers

Contents

Author’s Note

Introduction and Executive Summary

History of the Hiring Conundrum

Trends that Confound Hiring

Questionable Assumptions

· Assumption 1: Resumes (CVs) are effective job hunting tools

· Assumption 2: Exaggerated or false claims on a resume open more doors

· Assumption 3: The format and wording of a resume makes a significant difference in chances of getting hired

· Assumption 4: More skills = better quality jobs and higher pay

· Assumption 5: There is a magic formula for “standing out”

· Assumption 6: Job descriptions from hiring companies tell job seekers everything they need to know about a given position and a given company

· Assumption 7: Increased certification always makes a candidate more marketable

· Assumption 8: Job markets change slowly enough over time to make additional, formal training feasible and worth the expense and time.

· Assumption 9: Stuffing a job description with more requirements than a normal human being can reasonably perform increases the likelihood of finding more able candidates, or at least provides valuable market information on available candidates

· Assumption 10: Mass applications, both for jobs one is qualified to perform, and for additional jobs where one’s qualifications are marginal or non-existent, increases the chances of landing a real job

· Assumption 11: Job boards still work

Ineffective Hiring Solutions

· Assumption 12: ATS systems successfully filter unqualified job candidates for the company that uses them, so they can choose among a reasonable number of qualified candidates and make a successful hire.

· Assumption 13: In-house, corporate HR departments, are capable of finding sufficient qualified candidates to fill all but a few open positions.

· Assumption 14: Staffing companies can find willing and qualified contractors to fill open positions when their corporate customers fail to fill those positions.

· Assumption 15: Contract-to-hire is a viable and satisfactory way for customer companies to “try before buying” and recruit qualified talent.

Solutions that work

· For employers

· For job hunters and employees

Conclusions

Footnotes

Author’s Note

We recognize and readily acknowledge the complexity of the subject matter we confront in this article. While we would like to help with the matter at hand, namely, hiring, we recognize that there are significant issues, and attempt to analyze the concerns with hiring, towards a better understanding of the underlying issues inherent in the process.

No one likes to be laid off, particularly when the layoff is unjust, but the reality is that massive layoffs continue to happen, and speak to a perverse, pervasive and frankly horrible understanding of hiring, and the awful treatment of good human beings. Our thesis is that poor hiring practices, and the impunity of important decision makers, lies at the heart of the problem. Until the decision makers feel the consequences of their own decisions, industry will continue the morbid decline it has initiated, and will continue to fail.

Introduction and Executive Summary

Claim: We see the day approaching, when applying for jobs on job sites is no longer worth the effort, and posting jobs on those sites loses effectiveness. Additionally, the traditional resume / CV method of personal or business marketing appears to have diminishing relevance and effectiveness over time. It is possible, even likely, that traditional CV and traditional hiring processes have already passed their use-by dates and are now rotting in the refrigerator.

Clearly, this is bad news for job seekers, beginning entrepreneurs and employers. The fundamental problem turns on the amount of noise present in the job market, and the inefficient or even counter-productive business procedures at hiring companies. We believe the noise level to be loud enough, pervasive and so difficult to pierce through that we find a truly enormous, tragicomic, almost unfathomable Charlie Foxtrot embodied by the oft repeated, public laments of both employers and job seekers.

Employers complain that they can’t find qualified candidates to fill available, open positions and job seekers complain they can’t find good jobs. This is happening during a time when there are hundreds of thousands of unfilled positions awaiting successful candidates. A moment’s thought on the situation leads to the obvious and trite observation that, perhaps, both sides in this equation need to examine their assumptions carefully and change their respective strategies.

Of necessity, this article is long; the trends we examine are complex and difficult to understand, despite long and dedicated research on the matter. Regardless of this, we strongly recommend reading the entire article, even if in several sessions, since the particular viewpoint we favor is unfashionable, but likely probative. The article will be maintained and updated from time to time, as we consider this subject to be both very important and (elsewhere) unsatisfyingly understood and documented.

History of the Hiring Conundrum

Today: The collection of causes that lead to this near-calamity are poorly understood, as a fast perusal of articles written on the subject easily demonstrates. We discuss here recent employment history, say, over the last ten years, in an effort to uncover at least some of the important underlying factors that have lead to high levels of market noise confounding the hiring process.

This article from the Harvard Business Review agrees with many of the conclusions we find here, and, in some cases, goes much further than we do. A fast Google search on a phrase such as “something is wrong with recruiting and hiring practices” turns up a large collection of analyses over the last several years, with few positive in outlook.

We study these unfortunate circumstances and highlight some of the causes which created it. Potential solutions will be discussed in articles to be published in the near future. As the conundrum is large and pervasive, we doubt there is a single solution, and intend later to propose a collections of measures individuals and companies can take to mitigate the formidable obstacles to resolution of this dilemma.

Trends that Confound Hiring

Background: Several long-term, ponderous, one-way trends have slowly developed over the years to frustrate hiring, job-hunting and business opportunity mining. The part we think we see, that other observers miss, is that these noxious trends are mutually reinforcing, creating slow-moving but momentous, positive feedback circuits with large-scale, harmful consequences that resist individual efforts from all players to alleviate.

These issues are deeply embedded, resistant to change, systemic, institutional, and rely on multiple assumptions we believe to be false or questionable. To be precise, we evaluate assumptions to be false, when either statistically untrue (probability close to zero) or so much lower than expectations as to be practically false, in other words, a bad bet.

The issues include, but are not limited to:

an understandable, but ultimately corrosive, tendency by some job seekers to exaggerated, or even false, claims of capability on a resume;

increasing fragmentation of the job market in the direction of many increasingly narrow specialties, each requiring considerable practice and expertise, with a correspondingly smaller potential market and higher risk of extended unemployment and unfilled jobs;

"kitchen-sink" job descriptions, usually for contracting positions, specifying for a single position so many qualifications that it would take several people to realistically satisfy;

candidates applying for every job they might, someday, during a blue moon, qualify for (this is the "you never know" mindset), and;

worst of all, the widespread adoption of applicant tracking systems (ATS), in effect, artificial intelligence programs, often poorly trained and tuned, designed in part to filter the flood of hundreds of applicants for each available position.

In addition to these points, we’ll also comment on the perceived long-term decline in average quality of HR departments, professional staffing companies and the recruiters who work for them.

In a very real sense, we have all, entrepreneurs, job seekers, recruiters, business partners and employers, brought these trends upon ourselves. We see this as a massive example of the age-old tragedy of the commons, in which the individual, short-term, perceivable interests of the individual players gradually works against and corrupts the common good. Everyone suffers, and few understand the true nature of the problem.

Questionable Assumptions

Detailed examination of the above trends: At least some explanation of each of the above points are in order. We plan more detailed articles, with data or links to data backing up each point, sometime in the near future on our Substack.

In the meantime, this present editorial article serves as a summary of basic problems in job placement that we believe are practically immutable and irreversible. Elsewhere, we propose possible solutions, for both job seekers and employers.

Assumption 1: Resumes (CVs) are effective job hunting tools

Evaluation: false.

Massive over-application on the part of job many hunters dilutes the effect of the most qualified candidates, who become lost in the flood of applications;

ATS are used, probably erroneously, as filtering tools for incoming resumes, removing a large fraction of incoming applications from being considered or even seen by a human being.

Savvy candidates re-write their resumes for each job they apply to, to get a tight keyword match at least, in hopes of surviving ATS filtration. This causes a drift in meaning from their “generic CV”, e.g. their LinkedIn profile, which can raise HR eyebrows if compared to their profile.

Hiring companies are often less than careful to communicate with applicants, leading to frequent “ghosting” = no response, save for a possible, automated and immediate acknowledgement of the application. Ghosting causes poor candidate experiences, and is a disincentive to further applications.

End result: Poor matches between actual qualifications and job requirements caused by excessive noise in the process. This has led to CVs being necessary, but not sufficient, tools for both hiring and job-hunting.

Assumption 2: Exaggerated or false claims on a resume open more doors.

Evaluation: false.

Employers are well aware that some candidates are willing to exaggerate and falsify information on their resumes in hopes of getting further through the talent acquisition system, and so have instituted a number of checks to ensure that applicants actually fit the job requirements. These checks can take the form of written entrance exams, rigorous and possibly repeated interviewing, coding tests, and background checks.

Each of these methods is subject to error, and each can lead to poor candidate experience and delayed hiring. Thus, the presence of some dishonesty by some candidates leads to less-than-pleasant verification and validation steps for all candidates, and slows the hiring process considerably.

Assumption 3: The format and wording of a resume makes a significant difference in chances of getting hired.

Evaluation: conditionally true.

First, as explained below, the keyword match must be very high. We find using software such as Jobscan or Google’s Jobalytics, along with a lot of creative English skills, can, with about two to three hours concentrated labor per job application, create a resume with better than a 90% keyword match. AI resume-writing assistants might speed this process up quite a bit. That will typically get a resume past the first hurdle: the robot ATS intake machine. This is the first condition that must be met for a successful CV.

We estimate that keyword match percentage scoring is used by at least 46% of companies as of this writing. The number represents the consensus that a majority of applicant tracking systems use this scoring system combined with the consensus that about 90% of companies use some sort of ATS. Ten percent (10%) of companies, mostly small companies, don’t use ATS for hiring.

The remainder, 44% or less, use smarter ATS systems capable of at least some synonym recognition and semantic meaning analysis. We expect such systems to lie on a spectrum between crude keyword match scoring and AI-enhanced, sophisticated, advanced semantic analysis capable of grasping the meaning of both CV and job descriptions, compare the two, and score the match based on meaning. Alert candidates must assume a significant fraction of ATS systems are smart and write their resumes to also satisfy these systems. This is the second hurdle job seekers must pass, since companies rarely advertise which ATS system they use.

Assumption 4: More skills = better quality jobs and higher pay

Evaluation: conditionally true

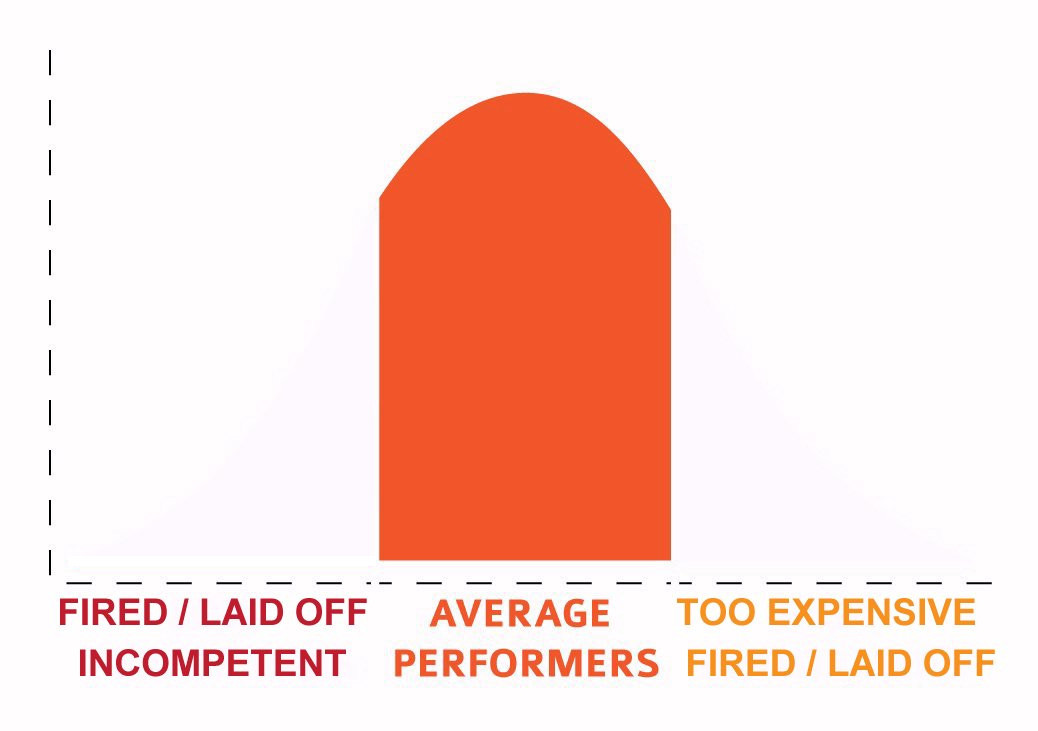

The third hurdle is reversion to the mean, usually understood to mean, by compensation. Mostly undocumented, but inferred by hundreds of experiments, are additional hiring rules which vary from company to company. We have concluded over the years that these rules have the effect, if not the intention, of selecting for candidates in the middle of the bell curve, roughly between -1 and +1 standard deviation from the mean.

Both tails are excluded; the left-hand tail considered inexpensive but too incompetent, the right-hand tail competent but too expensive. We compress possibly several variables into salary vs. proven ability to simplify this category of filters.

What this means in practice is that additional skills benefit junior and mid-level employees, up to a point. Hiring companies usually have staffing budgets they cannot exceed, limiting salary offers and creating downward pressure on salaries in general. Once a job hunter has amassed expert skills and expects higher pay to match, the number of opportunities decreases, due to cost. At some point, acquiring additional skills does almost nothing for the employee, since employers cannot pay for the additional skill sets.

Ageism also factors in, and a host of other, less easy to deduce factors. This bucket of selection criteria appears to be the second-level filter, and is both secret and subjective. Some aspects are also illegal, such as ageism, an excellent reason why this criteria bucket is usually unpublished.

Assumption 5: There is a magic formula for “standing out”

Evaluation: probably false

The last filter involves those resumes among the survivors that somehow “stand out”. Again, this is essentially subjective, but some differentiators are commonly touted as often successful. The resume should contain standard information, not be too far out nor incomprehensible, well written, but substantially different from the other surviving resumes considered.

We believe, but lack experimental data, that resumes with succinct “hook” sentences or paragraphs make the difference in this phase. This is the final, also subjective, criteria, and is important for transporting the resume over the finish line into interview territory.

The most effective resumes for the purpose of getting a decision maker’s attention start with a lead-off hook sentence in the summary at the very top of the resume succinctly announcing one or more noteworthy, attention-grabbing results achieved by the writer at a recent job. That single sentence consumes the 7 to 8 seconds of attention the decision making reader has to give, and makes the biggest difference: attract that attention, and the resume goes into the “maybe” pile. The rest go into the “no thanks” pile and are deleted or ignored.

Most of the time, given the state of typical management, attaining such a “hook” achievement at a typical job once is challenging. Making it a regular habit is very difficult, demanding sustained, deliberate effort on the part of the employee. In short, employees must constantly think about how their current job performance affects future employment, and so strive to manipulate their employment situations specifically to generate good-looking achievements for likely future jobs.

Between jobs, the resume writer has to wrack his or her brains and memory to find something both powerfully persuasive and truthful to say. This is the point where “creative” writing takes place. Truthfulness and attraction of attention appear to conflict. Everyone struggles with this balancing act.

The ATS systems, described below, render a large fraction of all applications moot and worthless. Results are not visibly better when applicants spent two to three hours per application tweaking resumes to satisfy the ATS robots. The resumes still appear to fall into a black hole, almost always, and some people eventually just give up in frustration. Exceptions do occur, but from the point of view of the job seeker, appear to be almost random events separated in time. Something fundamental about the process is broken, and we are by no means the first to take note of this fact.

Assumption 6: Job descriptions from hiring companies tell job seekers everything they need to know about a given position and a given company.

Evaluation: false.

It should be noted that job seekers, including the present writer, when reading a particular job description, rarely spend time looking up other JDs from the same company in the hopes of gleaning details about how that company views hiring and what their likely attitude towards employees might be. Moreover, although company reviews in both Indeed and Glassdoor have been available for a long time, job seekers do not routinely read all the reviews, especially if numerous.

Additionally, although the process is clumsy and difficult, it seems to us that a prospective candidate would do well to search LinkedIn to try to find out who is the hiring manager with the open job requirement at the hiring company and look up his/her history, and the history of his/her colleague managers. That might reveal whether there are corporate culture issues, particularly in the case where a company has a lot of turnover in individual contributors and first-line managers.

Is the position listed on the company website? Is it also listed on Indeed, GlassDoor, LinkedIn, etc.? Does this indicate that the company has a hard time hiring and / or retaining employees? Why? Time to start Googling!

Assumption 7: Increased certification always makes a candidate more marketable.

Evaluation: false.

Some certifications do enhance marketability, but for limited sub-markets and for limited time. An example category that comes to mind are most government agencies as customers. For them, required certification may not be a predictor of a candidate’s real ability, but is an excellent predictor of their acceptability by senior management, governing institutions and auditors. Additionally, certifications help a company quite a bit when building up for a company-wide certification, such as certain ISO designations.

Certifications tend to be worthless for cutting edge development companies where ability, creativity, experimentation, persistence and diligence are the weapons of choice. These companies select more for good verbal performance during interviews and successful coding tests, and largely ignore certifications and training.

Even if the niche a job seeker trained for looked good at the time, it can disappear while they are training for it, or sometime after, reasons mostly mysterious and often hard to discover. The job seeker complains they are highly qualified, but can't find a job anywhere, no matter how hard they try. There are no guarantees of fitness for a particular purpose, or even any purpose at all.

Assumption 8: Job markets change slowly enough over time to make additional, formal training feasible and worth the expense and time.

Evaluation: false.

We are reminded of a time not so long ago when a local, notoriously ill-managed company quietly laid off ten Oracle DBAs simultaneously. The incident barely made it into the news; we found out about it via an Internet rumor, and corroborated the rumor by searching for both the company on Google and the released employees on LinkedIn.

We happened to be looking for a job at the time, and realized, chillingly, since we were senior to all of them, that we would have to wait until all ten were hired before we stood much chance of finding a job. This single layoff temporarily created a sudden, localized, severe glut in this niche job market, one that took months to equilibrate.

The upshot was an intense realization that local job markets, over brief time intervals, are highly chaotic. The chaos is difficult to observe externally; we happened to get lucky this one time and gained a valuable insight, and the patience to persevere until the glut subsided. Additional training and certification in this case could not happen fast enough to matter, and wouldn’t have helped.

Assumption 9: Stuffing a job description with more requirements than a normal human being can reasonably perform increases the likelihood of finding more able candidates, or at least provides valuable market information on available candidates.

Evaluation: false.

We don't know why employers do this. We don’t apply for such jobs; by repeated experience, they are non-starters, and often represent fishing excursions by companies seeking to better understand niche candidate markets, rather than real jobs with any realistic chance of gaining employment. Worse, it can be incredibly difficult to craft a keyword match score on such a JD high enough to matter.

The problem with such fishing excursions is that valuable data gleaned from the test obsoletes rapidly. The people and the markets change and move.

We observe the exact same, over-specified job descriptions posted over and over, often for six months to a year, unfilled. Then, hilariously, we read endless complaints from employers that they can't find qualified people to fill the positions they have open. We wonder, why?

Assumption 10: Mass applications, both for jobs one is qualified to perform, and for additional jobs where one’s qualifications are marginal or non-existent, increases the chances of landing a real job.

Evaluation: false.

The worst consequence of overapplication is that employers routinely receive far more applications for a single job than can be processed. More than twenty years ago, we recall one manager telling us he trimmed the stack of resumes by arbitrarily throwing away all non-local candidates.

Nowadays, there is a more technological solution, one which we, with a lot of experience with artificial intelligence now, find particularly ineffective, risible and even counterproductive.

Ineffective Hiring Solutions

Assumption 11: Job boards still work

Evaluation: mostly false

Most job boards (Monster, Dice, Indeed, LinkedIn, Google Jobs, GlassDoor, CareerBuilder, many other smaller, niche boards) offer some sort of “one-click” application process, making applying for a job extremely fast and easy. It should not come as a surprise that this very same feature defeats its own purpose; it is so easy to apply for a job that many job hunters simply blow out their CVs to as many jobs as they can, creating massive over-application.

Some jobs receive as many as 1000+ applicants, a number that is clearly beyond any HR department’s capability to process. The wild over-application demands an automated solution; a way of filtering out applications from under-qualified applicants. This job is often delegated to ATS, as described below.

The issues with doing this are many; perhaps the most important of which is whether any machine can distinguish between good and bad applicants. The majority of ATS machines use keyword filtering, so that incoming applications are scored strictly on the basis of the number of keywords that appear (literally) in the application.

There are more sophisticated systems that have possibly AI-enhanced semantic analysis functionality, intended to extract and compare the meaning of the CV against the meaning of the job description. Our experience over the decades with both text parsing programming and AI lead us to believe that constructing such a system, which can reliably and repeatedly distinguish between good and bad applicants, is a tall order indeed.

Since both hiring managers and HR departments routinely make bad hires, as evidenced by the massive number and magnitude of recent layoffs that continue to make the news, and are still happening as we write this, we doubt that companies actually know what they are doing when it comes to hiring. Because mass layoffs have been happening for a very long time, our view is that, until companies awaken to the tremendous damage they do to themselves, their investors, and to the available applicant pools of potential employees, by continuing the hiring / mass layoff playbook, the knowledge of how to hire and retain good employees will remain elusive.

Put bluntly, their blundering makes it extremely difficult to program machines to do what people apparently cannot do. There is no way to gather good practices to train machines when humans routinely commit massive Charlie Foxtrots. Until that problem is definitively solved, so that large companies can show stable employment for the vast majority of their hires, we do not and cannot expect that machines can be trained to take over this responsibility.

Applicant tracking systems (ATS)

These are (possibly) AI enhanced, multiple-function, enterprise computer programs. Among other functions, they (a) receive incoming applications for a job, e.g. from LinkedIn, match the applicant with the specific job applied for, send an acknowledgement email, (b) filter those resumes using a pre-programmed scoring system, most often graded on the basis of percentage keyword match, (c) track the applicants as they pass through the system, stopping when an individual is filtered out, (d) possibly but not certainly, add unsuccessful applicants to a pool of potential future candidates, (e) convert successful candidates to employees and hand them over to a separate system designed to handle employees.

A very lively discussion of ATS systems on Quora can be found here. Both fans and detractors chime in, and there are many viewpoints expressed. Additionally, there is a reasonably recent list of 20 major ATS systems along with a matrix of their important properties.

We've seen estimates that almost 90% of companies of any substantial size, who do a lot of job posting, all use ATS. Due to the number of resumes they receive, they must.

Note the emphasized keyword match. There is a minimum keyword percentage match threshold that must be met before a human being, like HR or the hiring manager, ever sees the application or the CV. While we are aware of much more sophisticated, AI-enhanced ATS systems that understand synonyms and context, the majority still use raw keyword matching, and we can guess the less expensive options are all like that.

If 90% of all companies use ATS, and the majority use less expensive, keyword-matching options, we compute a 46% minimum chance of a job seeker encountering a keyword-matching ATS, in other words, nearly half the time. At 90% ATS adoption, that means a maximum of 44% chance of encountering a smart ATS that can parse a resume for meaning rather than keywords.

The remaining 10% of companies still use human beings to filter resumes. If hundreds of applicants apply for a job in that case, the people who must filter that pile down to a manageable size can’t spend more than a few seconds on each resume. Some recruiters of long experience explain that only the first 50 or so resumes were actually read in the days before ATS; the rest were retained as backups.

Assumption 12: ATS systems successfully filter unqualified job candidates for the company that uses them, so they can choose among a reasonable number of qualified candidates and make a successful hire.

Evaluation: false.

This process systematically rewards people who are very diligent, and possibly deceptive, at tuning their resumes, often using software to make the comparison and suggestions for missing keywords, not people who can successfully perform the job. These two groups typically have little overlap, as time spent on one activity competes with time spent on the other. Often people in the first category use AI to write their resumes.

Everybody else gets filtered out, regardless of accomplishments, regardless of ability. No one ever sees those resumes at the hiring company, and the applicants are instantly ghosted.

Repeat several hundred times on both sides. A few years ago, we were told by a hiring manager trying to fill a technical position, that the ATS system filtered out all applicants but two bus drivers.

We suspect that companies do not closely monitor the configuration nor performance of their ATS systems, since doing so with due diligence and reasonable, statistically significant quality control would obviate most of the savings to be had by using them in the first place. We’re confident most companies use ATS systems with their default configuration, perhaps set a keyword-match rejection threshold largely based on available interview time, and merrily forget about it after that.

Having had a lot of recent experience with artificial intelligence, we find this practice simultaneously appalling and hilarious. The result is predictable: employers complain that they can’t find qualified people and job seekers complain that they can’t find a job. Doh!

Result: mediocrity. This is stupid, because computers are stupid. What does this reveal about companies that rely on these systems for vital business decisions like hiring?

Decline in average quality of professional recruiters: We emphasize that we are not attacking individuals nor specific companies here, but observing overall trends over time.

Assumption 13: In-house, corporate HR departments, are capable of finding sufficient qualified candidates to fill all but a few open positions.

Evaluation: false.

In-house recruiting: Corporate, in-house recruiters, whether FTE employees or contractors, long ago descended into recruiting mediocrity on the average, mostly driven by huge numbers of applicants and the increasing need for HR departments to spend increased time on complicated employment law compliance. We see the job descriptions for HR positions all the time: the most important word in each JD is always compliance.

Compliance is a very different skill set than recruiting, and it used to be the case that there was a separate department, often referred to as the Personnel department, that handled compliance issues and managed such things as hiring, firing and layoffs - reductions in force (RIF). No more - both recruitment and compliance are now typically rolled into one, large, HR department. This may be cost-efficient, but is unlikely to be functionally effective, as explained next.

HR employees are rarely rewarded for presenting successful candidates, since that is one of their basic job descriptions, and they just can't care that much about filling any particular job, due to time pressures and, rightly, feeling the principal responsibility belongs to the hiring manager. They work statistically, opting for the highest possible score on the yardstick used to judge them, and so preferentially pick the easiest hires rather than the most critical ones.

HR, and the ATS systems they use, depend most often on the literal wording of the job description, not its meaning. They don’t know what the positions mean, have no context, and are neither incentivized nor paid enough to know. ATS systems are headless, mindless, soulless robots, strictly bound by programming, utterly devoid of understanding, regardless of the power of the AI driving them.

Add the additional HR compliance duties, their traditional functions as employee resources when the employees need help, and mediators in disputes between employees and management, HR people have less attention and time left to devote to recruiting alone.

They can't recruit that well because they are not incentivized to do so. They have multiple, often conflicting duties and must balance their time between these duties. Their management sometimes provides policies to guide balancing and priorities, but the important point is they have a lot to do in little time, and the fraction of their time devoted to recruiting job candidates is significantly smaller than it used to be.

The loss of effectiveness of HR as recruiters creates additional, difficult-to-analyze market noise. Employers simply hold their collective hands out, palms up, refuse requested raises, lowball prospective candidates, fail to promote from within, and periodically adjust “normal turnover” upward to match whatever they happen to experience. After all, managers do the exact same job-hopping. It’s the only way they can progress, too.

Enter professional staffing companies, often organized into two camps, recruiting specialists and compliance specialists. These companies specialize in searching for candidates, screening them, doing the initial interviews, perhaps preparing good quality candidates for interviews with the hiring companies.

Compliance work normally kicks in only after the recruiting process has been successfully completed. Most often, the successful candidates will hire on as employees of the staffing companies and contractors to the hiring (customer) companies. The staffing company then also functions as a payroll and billing service.

This last situation, placement of staffing company employees in a customer company, places contractors in a fundamentally awkward spot. They are not viewed as true colleagues by their peers at the customer companies, but as temporary, disposable hired help. Abuse, particularly in the form of sudden, unannounced termination, is likely and common.

The staffing company rarely monitors their placements very closely, and in disputed situations, most often will take the side of their customer companies over their own employees, regardless of justice nor the actual reality on the ground. We've been there many times, and refuse to work under those conditions, unless given contractual, up-front monetary damages in case of company breach or reversal.

Needless to say, most staffing firms won't agree to this, because their customers won't agree to it. The very disposability of contractors is their only market advantage given the increased cost caused by a third party in the deal. The better average capability of contractors is already priced into the deal, and, because of the higher price tag, expected rather than appreciated.

Assumption 14: Staffing companies can find willing and qualified contractors to fill open positions when their corporate customers fail to fill those positions.

Evaluation: mostly false.

Staffing firms often do not use ATS systems. The recruiters manually and pro-actively look for candidates themselves, almost always with LinkedIn searches, under the reasonable presumption that they received the job position to fill only after the customer company repeatedly failed to fill the position.

As a side note, staffing companies typically take the job descriptions and salary requirements as received from their customers very literally, with scant wiggle room for negotiation, presenting to candidates the same take-it-or-leave-it milieu that failed when the customer company attempted to staff the position themselves. In fact, the monetary considerations are more constrained due to the increased cost incurred by using a staffing company in the first place.

While a staffing firm may look like a reasonable solution when it comes to matching a unicorn candidate with a unicorn position, it has inherent risks. The recruiting job is very difficult, since the customer company already failed to find matching and adequate candidates, so the staffing company failure rate is high, and consequently turnover, both among staffing firm recruiters and the contractors they place, is high. We’ve seen it among contractors and recruiters we know, over and over again: they change jobs frequently.

How do we know this? Because customer companies rarely farm out an open position to just one staffing company. Much more frequently, they send their unfilled REQs to three to five companies. We always receive multiple contacts for the exact same job. In this case, it is the early bird, with respect to us, that catches the worm.

A moment’s thought on this practice reveals that while running a job through multiple staffing companies might slightly increase the chances of hiring for the customer company, it decreases the chances of success for the staffing company drastically. In the above scenario, each staffing company starts out with only a statistical 20% to 33% chance of success.

Add to that the difficulties of finding a qualified candidate, first, before other, competing staffing companies make their pitch to the same candidate, for the exact same position. The candidate must be willing to work as a ”foreign” contractor under financial and requirement constrained, potentially hostile circumstances, and nearly certain below-market pay. We conclude that the resulting hire, if it happens at all, is either a stroke of luck (unlikely) or the candidate must be distressed and sub-optimal.

Assumption 15: Contract-to-hire is a viable and satisfactory way for customer companies to “try before buying” and recruit qualified talent.

Evaluation: false.

Contracting, particularly contract-to-hire, is commonly practiced. Most successful contractors won’t buy the hire part, since they can do math, and simply keep their skill sets marketable and continuously look for their next job; they know they’ll be first on the chopping block when the fecal matter hits the rotating blades.

Companies in the last several years have exhibited increased interest in hiring employees themselves and decreased emphasis on contractors, leading to longer unfilled position times and increasing average time-to-hire. Part of this phenomena has come from the palpable decrease in competence and diligence among recruiting firms and their employees. Staffing companies experience business failures and higher turnover because their customers now place more emphasis on hiring employees themselves.

Our observations over the years have witnessed a gradual decline in quality of professional recruiters, likely from poorly designed incentive systems, emphasis on numbers to compensate for risks, a "body-shop" company culture, mediocre management, poor customer commitment to the process and high turnover among colleagues, resulting in lots of unhappy contractors and unhappy customers. Sustained, intractable, industry-wide issues with professional staffing companies has gradually culled the herd of able and willing participants, leaving obedient, possibly diligent and hard-working, but unimaginative and risk-adverse mediocrities in their place.

Solutions that work

Of course, hiring is still happening, but at a much slower rate than both employers and prospective employees would like to see. We offer a few of the many possible ways to improve outcomes for both, and observe that plenty of companies and candidates are already using these methods.

We expect that companies which take the time and effort to thoroughly examine and re-engineer their hiring practices will be among the survivors in the mid to long-term; but cannot assign an absolute value to such re-engineering and unconventional methods. We are convinced hiring and retention are crucial, since nearly all the low-hanging business fruits have already been picked - technological progress in particular gets more difficult over time.

The fact that adoption of these unconventional techniques is slow is largely a function of inertia; companies are often under-staffed, job-holders are usually very busy, often stressed, and lack the time and energy left over from hectic schedules to innovate, especially for something as prosaic and unsexy as recruitment and hiring.

For employers

Detailed and objective examination of the entire hiring process, from initial formulation of a job opening and its description, through talent acquisition outreach, candidate qualification, interviewing techniques, selection criteria and job offer formulation. Once completed, this process allows for engineering of the hiring process for optimization purposes, maximizing value while controlling costs.

De-emphasis of publicly available job advertisements in favor of quiet, proactive talent sourcing techniques, enabling improved confidentiality in hiring, prequalification of candidates, higher quality hiring, drastically improved candidate experiences, better retention and lower turnover, and reduced expenses due to job advertisements and expensive applicant tracking systems.

De-emphasis or complete removal of ATS from candidate filtering, re-purposing such systems for the purpose they were originally designed: tracking applicants as they progress through the hiring process.

Division of Human Resources departments into two mutually exclusive sectors: recruiting, tasked exclusively with talent acquisition, and compliance, which only handles regulatory and legal compliance concerns. Reductions in force, if necessary, would be administrated by the latter.

For job hunters and employees

Strong understanding of conventional job hunting tactics, when appropriate, and when not;

Conscious understanding of the need for quantifiable achievements in current job to pave the way for better resume points targeted at future jobs;

Development of unconventional job hunting tactics, centered around gradual and structured development of relationships with potential future employers;

Development of a list of most desirable companies for future employment, and ongoing and thorough research of those companies, and creation of company dossiers to facilitate development of future relationships with individuals in those companies.

Conclusions

Lying and exaggeration on resumes perpetrated by some job candidates prompts more intensive employer verification for everyone, and, consequently, longer hiring times due to this one practice alone.

Cost and complexity concerns among employers motivate ever narrower employee job function niches, i.e., fragmentation, with lower pay, requiring constant re-education and often re-certification among job seekers, making pay increases as a result of sustained effort and accumulated expertise difficult to obtain, motivating a high degree of turnover. From the employee point of view, their potential job market shrinks over time, increasing their risk of unemployment, motivating excessive emphasis on ephemeral certifications and over-application for jobs.

This fragmentation of the job market into ever more narrow job descriptions is also a major source of employee burnout, mental health issues and turnover. It also motivates the now-old, tried and true attitude among employees that “ya gotta move out to move up”. We ourselves have seen this over and over, and done it many times ourselves.

The increased cost of contractors compared to employees incentivizes increased expectations from employers, mostly balancing their usual increased productivity and skills, leaving only their ready disposability as a market advantage. Hiring contractors that can be dismissed on short notice helps employers prevent some reductions in employee forces and helps with turnover rates, since contractors are not counted as employees.

To compensate for the increasing amounts of time it takes for someone to get a job, job seekers apply for hundreds of jobs before getting even one interview. This results in employers receiving hundreds to over one thousand applicants for one job, clearly an unmanageable number.

The companies respond to this over-application phenomenon by the increased use of automation in the form of applicant tracking systems, filtering out the bulk of applications, mostly by keyword-match scores, before any real person at the hiring company ever sees a resume. Employers using ATS quickly and permanently lose touch with the actual, available pool of real human beings, and live in an abstract, phantom world of job descriptions and salary categories.

More applications implies more ATS filtering implies even more applications implies even more ATS filtering, ad infinitum. This is the largest and most harmful mutual trend amplification.

As we hope we have demonstrated, these pernicious trends indeed feed on and amplify each other, and serve to make job and candidate matches, and the resultant hiring, slower, more painful and less successful. Job seekers get sick and tired of the unpleasant, unrewarded, sustained effort, of the salary low-balling, the hostile and difficult interviewing, and the stress and uncertainty this increasingly broken process generates. They leave the market in numbers large enough to be noticed; see the “Great Resignation” for numerous examples and counterexamples.

Eventually, they realize they might as well become YouTubers and start yet another cooking channel. More power to them!

Potential solutions to these issues will be covered in an upcoming article. Stay tuned!

Footnotes

More information about Overlogix can be found at Welcome to Overlogix! Our Substack, now our main content repository, is online and available for browsing. An index of Substack articles can be found at this link.

Our online portfolio can be found at our LinkedIn master index. Our articles on applied AI are indexed at our Applied AI index, business topics at our B2B Business Index, and our TL;DR series of rapid introductions to AI and related topics lives at our AI Mini-Wiki. Critical information on getting a job are detailed at our Getting a Job index. AI news, including our list of curated links to articles of interest, can be found at our AI News page.

Thanks for reading! More to come!